Recently I got to use the new Divvy bike share system in Chicago.

When I'm nervous on a bike, as I was in this case because I don't usually bike when I visit Chicago, I tend to ride as fast as I can. I found that I couldn't keep up with traffic on the three-speed Divvy cruiser; even in my silly cowboy boots I had greater pedaling potential than the little chain ring could realize.

But

for the short ride, my limited speed didn't seem to matter. No motorists honked at me

or swerved dangerously close to me as they passed, even though I saw many examples of the kind of behavior that angry road users point to as evidence of bike users being jerks. I would stop at red lights, only to be overtaken by men who pushed forward, looking to see if the intersection was clear and proceeding through when it was. Traffic signals applied not to them, it seemed, but to the taxi drivers who similarly pushed forward and stopped only reluctantly when bodies passed in front of them. I had noticed before how people, whether on foot, on bikes, or in cars, push forward into intersections with more gusto east of the Rockies than they do in the west that I know.

What I'm getting at is that bike share systems go into place in spaces where there are existing

standards of road behavior, and having access to the bike itself doesn't necessarily give you access to those standards. Not only do built environments suggest to us how to use a given road space, we carry with us ideas about what should happen there. I'm not pointing this out as some grand flaw in the bike share model, but rather to illustrate an academic concept. In processing my experiences as a bike advocate in Los Angeles, I started thinking in terms of the "body-city-machine" because I found that riding a bicycle involved at least three components: a human body with a particular worldview, specific kinds of technologies for riding, and a shared street. I came to the body-city-machine from theory about sociotechnical "assemblages," which describe how action happens in the world through more than individual bodies: we form "alliances" with objects. This is how many bike researchers, such as Zack Furness and Luis Vivanco, talk about the social life of bicycling. What I've tried to understand through the body-city-machine assemblage is what kinds of mobile places people create as they travel, building on the ideas of researchers like Justin Spinney that the street is not a space devoid of meaning.

I developed the body-city-machine concept to suggest a more holistic perspective for mobility in general. But because I do most of my thinking through bicycling, I'm also interested in how the idea can help create more inclusive advocacy and programming. As activists, we usually focus on one aspect of this equation. In vehicular cycling, for example, the emphasis is on the body: making the body fit to use existing roads. Lots of bike advocates feel that this model excludes people who don't fit a certain type because they recognize that there are many kinds of bodies using bicycles.

What I have seen in my years as a bike advocate is that most of my

collaborators focus on changing how people use streets through

changing the design of the street itself. In this paradigm, the emphasis is on the city: designing environments that are expected to stimulate behavior changes. I have concerns about this model because it has become part of a "creative economy" strategy that actually fails to provide economic opportunity for most people. As much as a Jane-Jacobsian vision of quality public spaces is a nice ideal, the reality is that our public spaces are surrounded by privately owned parcels and structures whose value fluctuates. What's good for the property owner may not be good for the unemployed or low-income bike user.

In addition to these concerns, though, it could be that I am not as convinced by the need for infrastructure because I'm a very empowered urban cyclist, and while I prefer to

ride on quieter streets, I'm comfortable taking the lane in traffic.

I've observed quite often that bike experts speak from their own experiences and expect others to share their perspectives, and I'm certainly not immune to that. In my work this tendency is actually an explicit strategy because ethnographers work backwards from experience to try and identify underlying patterns to behavior. I've been an ethnographer among bike advocates for some years, and I can vouch for the fact that bike professionals, too, are body-city-machines.

What I am seeing now, in my conversations with other advocates of color

as a member of the League of American Bicyclists' equity advisory

council, is what innovation can occur when people bring their varied experiences and cultures to bike advocacy. I realized in conversation with Eboni Hawkins

and Anthony Taylor that a shared identity across other

lines might help blur the lines between different kinds of bicycling. A

recreational cycling club, something I hadn't thought of as

an advocacy organization, could be interested in promoting more

transportation cycling among people who see having to use bikes as an indicator of low status.

If the ultimate goal is to change human behavior, why should street design be our only option? Unlike environmental projects, such as bike lanes and cycle tracks,

bike share programs seem to focus more on the machine part of the equation: making bicycles available for use. Similarly, open street events also change how people share

streets through manipulating what technologies one can use to travel in

them.

Of course, it's hard to really separate these elements; that's the whole point of the body-city-machine concept. For example, the placement of bike share stations is a spatial issue, and Chicago seems to have a lot of discussion going on around their bike projects seeming more symbolic than useful and a need for equity. But bike share does help illustrate how we can experiment with the constituent elements of the body-city-machine. I'd like to see more advocacy strategy that starts with bodies, not necessarily as effective cyclists, but as social actors in a

shared space. I'd like to see more incorporation of diversity at a

strategy scale, rather than hearing about campaigns that ask leaders of color to say yes to preconceived projects. I'd

like to see what happens when we make room for a diverse range of body-city-machines to participate in redefining what bicycling means.

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

Friday, September 6, 2013

Is the Bike Movement Too Cynical for Social Justice?

There's a need for a wider range of voices in the bike movement, and I know

that at least some key people are working to create a social justice

space. However, I think the struggle for social justice is being impeded by political correctness. Not political correctness itself, but fear of it. Fear that working to build more inclusive institutions is a distraction from something more important.

Flipping through a recent issue of the New Yorker, I came across an article about a white curator, Bill Arnett, who has for years pushed the art world to take African-American outsider artists seriously. The article focused particularly on the artist Thornton Dial, and the author, Paige Williams, commented that, "it can be tempting to ascribe Dial's rise to political correctness, but his work is strong enough to counter such skepticism." In other words, this artist's popularity might only indicate that his skin color makes admiring his art something laudable in the art world. Similarly, I have been told twice recently that gestures toward social justice made by institutions must be hollow attempts to satisfy some perceived demand for that sort of thing. The speakers in both cases were middle-aged, white men. One was talking about an institutional diversity initiative at a liberal arts college, and one was talking about bike advocacy organizations. This is what people have thought it's appropriate to say in front of me. Who knows how my reputation is dismissed behind my back with words like political correctness. Do you know what it's like to hear that your concerns are unworthy of the attention some people can take for granted, simply because you aren't the right color?

I would call this not skepticism, but cynicism: a cynical belief that any people of color who gain the attention of powerful institutions must be a front for white people's interest in political correctness, and it's a problem. It's awfully demeaning, and has added yet another barrier to inclusiveness across lines of race/class. What is particularly weird about this cynicism is the way that it is espoused by seemingly liberal individuals, who would otherwise shrink from accusations of racism. It almost seems like an effort to show how un-racist they are, as though somehow the PC champions of POC are the racists for making room for difference. The cynics see past this to...what, exactly? To me, it sounds like a profound denial of the need for restructuring many institutions that have benefited whites over others.

It might look unfair to attach a job or seat on a board of directors to somebody's skin color or gender. The key is that what might seem fair to you could be based on the position you inhabit, as a raced, classed, and gendered individual. We're not standing on level ground; the way that our world has organized access to resources means that we're on a hillside, and you may be closer to the top than some others simply because of the conditions into which you were born. Not only did you get a head start, but maybe you've been aided by your uncle's friend showing you the trailhead, or your classmate's father giving you a deal at the trail supply store he runs. There are two questions about social position to consider, in any field: how what you look like, how you act, and who you know got you to where you are and, on the flip side, how not looking and acting and knowing the right stuff keeps others from getting there. Racial difference can be expressed in the most subtle gestures, the most casual words, that reinforce the distance between us. If you're already near the top of the peak, it might not move you, but if you're down at the bottom you might be set back once again.

We're social creatures; we help our friends. Why is it a bad thing to recognize that one's circle is limited, and that it might take work to make connections beyond it? Why would it be bad to have a wider network from which to draw help with advocacy projects? The thing is, if you have a pretty limited circle from which to draw, you're not necessarily going to craft a message or programming that's appealing to a wider audience, because you have no idea what that wider audience cares about. And for a social movement, which would seem to want to get more people on board, that's a strategy fail. It is not a distraction from something more important to discuss race and class in the bike movement because Americans are hardly a homogeneous bunch. If you're not interested in the different experiences of the people you're targeting, why would they care about this bike thing you're into?

For far too long people without much interest in experiences other than their own have dominated the room, assuming that we all agree that aspiring to Copenhagen is best, or that all women want to wear heels on their bikes. They've been allowed to make their perspectives into THE perspective, leaving aside the social conditions that make Eurocentric visions of cultural supremacy seem normal, or that perpetuate expectations of gendered behavior. The philosopher Donna Haraway calls this the "god trick," a view from nowhere that allows particular people to claim that their experience is objective reality.

The continued championing of one narrow vision of bicycling has had at least one real effect: instead of us all seeing driving and suburbanization as a common enemy, embattled communities see bicycling and other sustainable practices as unwelcome symbols of power and privilege. The return to the city of the children and grandchildren of white flight is not a separate issue from urban renewal's undemocratic subsidy of destroyed urban neighborhoods. Bicycling is not a separate issue from oil dependency and superstorms. Road safety is not a separate issue from racist and classist structures of social status and the norm of expressing how wealthy you are through the kind of car you drive. The unremarked deaths of immigrants using bikes is not a separate issue from the outcries for safety that follow white cyclists dying. The use of bike infrastructure as an economic development strategy is not a separate issue from the lack of jobs with decent wages. The status displayed through driving is not a separate issue from social inequality. The anger some motorists express when interacting with bicyclists is not a separate issue from gentrification.

The segregation encouraged and enabled by the federally subsidized suburbanization of the United States still impacts our cities today. We have all been affected by it, negatively or positively, and belittling the importance of including the concerns of the negatively affected groups in favor of carrying out the desires of the positively affected groups sets us against each other once again. It's time to address the social side effects, the barriers to bicycling that show how it connects to wider frameworks of race and class bias. It's time to confront the use of bike infrastructure as a gentrification strategy, with the narrow vision of economic development that model suggests. If this stuff is a distraction from something more important in the bike movement, maybe the bike movement's not really that important.

Flipping through a recent issue of the New Yorker, I came across an article about a white curator, Bill Arnett, who has for years pushed the art world to take African-American outsider artists seriously. The article focused particularly on the artist Thornton Dial, and the author, Paige Williams, commented that, "it can be tempting to ascribe Dial's rise to political correctness, but his work is strong enough to counter such skepticism." In other words, this artist's popularity might only indicate that his skin color makes admiring his art something laudable in the art world. Similarly, I have been told twice recently that gestures toward social justice made by institutions must be hollow attempts to satisfy some perceived demand for that sort of thing. The speakers in both cases were middle-aged, white men. One was talking about an institutional diversity initiative at a liberal arts college, and one was talking about bike advocacy organizations. This is what people have thought it's appropriate to say in front of me. Who knows how my reputation is dismissed behind my back with words like political correctness. Do you know what it's like to hear that your concerns are unworthy of the attention some people can take for granted, simply because you aren't the right color?

I would call this not skepticism, but cynicism: a cynical belief that any people of color who gain the attention of powerful institutions must be a front for white people's interest in political correctness, and it's a problem. It's awfully demeaning, and has added yet another barrier to inclusiveness across lines of race/class. What is particularly weird about this cynicism is the way that it is espoused by seemingly liberal individuals, who would otherwise shrink from accusations of racism. It almost seems like an effort to show how un-racist they are, as though somehow the PC champions of POC are the racists for making room for difference. The cynics see past this to...what, exactly? To me, it sounds like a profound denial of the need for restructuring many institutions that have benefited whites over others.

It might look unfair to attach a job or seat on a board of directors to somebody's skin color or gender. The key is that what might seem fair to you could be based on the position you inhabit, as a raced, classed, and gendered individual. We're not standing on level ground; the way that our world has organized access to resources means that we're on a hillside, and you may be closer to the top than some others simply because of the conditions into which you were born. Not only did you get a head start, but maybe you've been aided by your uncle's friend showing you the trailhead, or your classmate's father giving you a deal at the trail supply store he runs. There are two questions about social position to consider, in any field: how what you look like, how you act, and who you know got you to where you are and, on the flip side, how not looking and acting and knowing the right stuff keeps others from getting there. Racial difference can be expressed in the most subtle gestures, the most casual words, that reinforce the distance between us. If you're already near the top of the peak, it might not move you, but if you're down at the bottom you might be set back once again.

We're social creatures; we help our friends. Why is it a bad thing to recognize that one's circle is limited, and that it might take work to make connections beyond it? Why would it be bad to have a wider network from which to draw help with advocacy projects? The thing is, if you have a pretty limited circle from which to draw, you're not necessarily going to craft a message or programming that's appealing to a wider audience, because you have no idea what that wider audience cares about. And for a social movement, which would seem to want to get more people on board, that's a strategy fail. It is not a distraction from something more important to discuss race and class in the bike movement because Americans are hardly a homogeneous bunch. If you're not interested in the different experiences of the people you're targeting, why would they care about this bike thing you're into?

For far too long people without much interest in experiences other than their own have dominated the room, assuming that we all agree that aspiring to Copenhagen is best, or that all women want to wear heels on their bikes. They've been allowed to make their perspectives into THE perspective, leaving aside the social conditions that make Eurocentric visions of cultural supremacy seem normal, or that perpetuate expectations of gendered behavior. The philosopher Donna Haraway calls this the "god trick," a view from nowhere that allows particular people to claim that their experience is objective reality.

The continued championing of one narrow vision of bicycling has had at least one real effect: instead of us all seeing driving and suburbanization as a common enemy, embattled communities see bicycling and other sustainable practices as unwelcome symbols of power and privilege. The return to the city of the children and grandchildren of white flight is not a separate issue from urban renewal's undemocratic subsidy of destroyed urban neighborhoods. Bicycling is not a separate issue from oil dependency and superstorms. Road safety is not a separate issue from racist and classist structures of social status and the norm of expressing how wealthy you are through the kind of car you drive. The unremarked deaths of immigrants using bikes is not a separate issue from the outcries for safety that follow white cyclists dying. The use of bike infrastructure as an economic development strategy is not a separate issue from the lack of jobs with decent wages. The status displayed through driving is not a separate issue from social inequality. The anger some motorists express when interacting with bicyclists is not a separate issue from gentrification.

The segregation encouraged and enabled by the federally subsidized suburbanization of the United States still impacts our cities today. We have all been affected by it, negatively or positively, and belittling the importance of including the concerns of the negatively affected groups in favor of carrying out the desires of the positively affected groups sets us against each other once again. It's time to address the social side effects, the barriers to bicycling that show how it connects to wider frameworks of race and class bias. It's time to confront the use of bike infrastructure as a gentrification strategy, with the narrow vision of economic development that model suggests. If this stuff is a distraction from something more important in the bike movement, maybe the bike movement's not really that important.

Thursday, August 8, 2013

Family Biking and Tacit Knowledge: The Ethics of Ethnography for Hire

Dear bikey friends,

Keep in mind that you are going to be mined for data as a valuable source of knowledge as more of the global corporate structure decides that biking for transportation is marketable.

My friend Davey Oil, who I've fangirled about on this site before, lives in Seattle. He and his partner have two adorable children, and Davey has a lot of experience in the kids and family bike world. Davey writes a blog called Riding on Roadways where he frequently shares about his experiences biking with his kids, and he ran the adult and volunteer programs at the kids education organization Bike Works for many years. As a wildly charming and well-appointed gadabout, he is something of a mascot for this community. This morning I dragged myself out of my dissertation haze long enough to find out why Davey had contacted me yesterday, and saw that he had found a project online called "Family Bike Life." This project has a clean, stylish website that asks people who practice family biking to share their insights and tips. The website says that the people gathering this information are "obsessed" with family biking, framing themselves as thirsty for knowledge.

Davey looked further into the project and found that it is part of something called the Lead User Innovation Lab, which lists IKEA as a partner, and is housed within a larger firm called Interactive Institute Swedish ICT. So is the design firm thirsty for knowledge because of personal interest, as the term "obsessed" would imply, or are they looking for family bike stories that they can deliver as a product to a client?

A network such as the family bike folks shares ideas through its social events and active life online. And, being willing and able to experiment with something many Americans see as impossible, they want to share their knowledge with more people. More and more bike shops are opening with family biking as the focus. This is a community that wants to make it possible for more people to ride bikes with kids, and from what I've seen as an outsider, they're also pretty darn media-savvy about how to do that.

But should the knowledge that they've formed as a community become a source of value to a firm with no social connections to the family bike network? On their website, under a tab entitled "Our Offer," Interactive Institute Swedish ICT gets down to business: "We explore future user experiences through human-centered information and communication technology. With our unique expertise in visualization and interaction design we create business opportunities in new and existing markets." Based on this description of their firm's services, the Family Bike Life project seems to be asking family bike enthusiasts to give away information that Interactive Institute Swedish ICT can package and sell.

This caught Davey's eye because he is about to open a shop, the G & O Family Cyclery. I got to hear about this project over the last year while it developed, and I know that Davey plans to create a space where knowledgeable people like him can make family biking more accessible for more families. Opening a bike shop is a strategy for achieving this. And I know that he in no way wants to keep others from family biking by guarding this knowledge; that is not the issue here. The issue here is framing one's corporate research activity as a feel-good "share your experience" survey, when the firm gathering the data plans to sell it as a product to some other entity.

Of course, I'm an anthropologist, so I do think that there is a lot of value to using ethnographic methods to investigate the less quantifiable aspects of social and cultural life. I do want to see ethnography taken seriously as a means to make change. But instead of empowering the family bike community to take their message further, Family Bike Life's firm appears to be packaging the information people volunteer as a deliverable. I am reminded, of course, of Graeme Wood's article about ethnography at design firms that made the rounds earlier this year. But, closer to home, my mind also goes to my own research, which focuses on how bicyclists become "human infrastructure" by sharing exactly the kind of information that this firm is trying to mine.

Jean Lave and Etienne Wegner's very influential concept of the "community of practice" seems to be at the heart of this firm's project, where they recognize that the family bike subculture transmits information between its participants without necessarily sharing it with the public. The entry point for this firm has been the subculture's desire to share their knowledge with others who appear interested. The anthropologist Julia Elyachar has been doing fascinating research on what is made possible by "tacit knowledge" in Cairo. Her writing has emphasized the embodied nature of these forms of knowledge, how people take action through informal systems and social networks. And these forms of knowledge are increasingly being seen as something valuable by the global development network.

How do we claim the human infrastructure we produce, and then also share it more widely? It is part of our communicative ability as humans that material objects take on symbolism which can circulate beyond the original social contexts of production. We don't have to give consent for people to use our ideas or images in public spaces. It's much easier to find examples out there that show how to exploit subcultures rather than empower them, given our capitalist economic system where everything that isn't copyrighted is fair game to manufacture and sell. I'd love to hear others' ideas about how to keep tacit knowledge tied to making communities of practice by making them more inclusive.

Keep in mind that you are going to be mined for data as a valuable source of knowledge as more of the global corporate structure decides that biking for transportation is marketable.

My friend Davey Oil, who I've fangirled about on this site before, lives in Seattle. He and his partner have two adorable children, and Davey has a lot of experience in the kids and family bike world. Davey writes a blog called Riding on Roadways where he frequently shares about his experiences biking with his kids, and he ran the adult and volunteer programs at the kids education organization Bike Works for many years. As a wildly charming and well-appointed gadabout, he is something of a mascot for this community. This morning I dragged myself out of my dissertation haze long enough to find out why Davey had contacted me yesterday, and saw that he had found a project online called "Family Bike Life." This project has a clean, stylish website that asks people who practice family biking to share their insights and tips. The website says that the people gathering this information are "obsessed" with family biking, framing themselves as thirsty for knowledge.

Davey looked further into the project and found that it is part of something called the Lead User Innovation Lab, which lists IKEA as a partner, and is housed within a larger firm called Interactive Institute Swedish ICT. So is the design firm thirsty for knowledge because of personal interest, as the term "obsessed" would imply, or are they looking for family bike stories that they can deliver as a product to a client?

A network such as the family bike folks shares ideas through its social events and active life online. And, being willing and able to experiment with something many Americans see as impossible, they want to share their knowledge with more people. More and more bike shops are opening with family biking as the focus. This is a community that wants to make it possible for more people to ride bikes with kids, and from what I've seen as an outsider, they're also pretty darn media-savvy about how to do that.

But should the knowledge that they've formed as a community become a source of value to a firm with no social connections to the family bike network? On their website, under a tab entitled "Our Offer," Interactive Institute Swedish ICT gets down to business: "We explore future user experiences through human-centered information and communication technology. With our unique expertise in visualization and interaction design we create business opportunities in new and existing markets." Based on this description of their firm's services, the Family Bike Life project seems to be asking family bike enthusiasts to give away information that Interactive Institute Swedish ICT can package and sell.

This caught Davey's eye because he is about to open a shop, the G & O Family Cyclery. I got to hear about this project over the last year while it developed, and I know that Davey plans to create a space where knowledgeable people like him can make family biking more accessible for more families. Opening a bike shop is a strategy for achieving this. And I know that he in no way wants to keep others from family biking by guarding this knowledge; that is not the issue here. The issue here is framing one's corporate research activity as a feel-good "share your experience" survey, when the firm gathering the data plans to sell it as a product to some other entity.

Of course, I'm an anthropologist, so I do think that there is a lot of value to using ethnographic methods to investigate the less quantifiable aspects of social and cultural life. I do want to see ethnography taken seriously as a means to make change. But instead of empowering the family bike community to take their message further, Family Bike Life's firm appears to be packaging the information people volunteer as a deliverable. I am reminded, of course, of Graeme Wood's article about ethnography at design firms that made the rounds earlier this year. But, closer to home, my mind also goes to my own research, which focuses on how bicyclists become "human infrastructure" by sharing exactly the kind of information that this firm is trying to mine.

Jean Lave and Etienne Wegner's very influential concept of the "community of practice" seems to be at the heart of this firm's project, where they recognize that the family bike subculture transmits information between its participants without necessarily sharing it with the public. The entry point for this firm has been the subculture's desire to share their knowledge with others who appear interested. The anthropologist Julia Elyachar has been doing fascinating research on what is made possible by "tacit knowledge" in Cairo. Her writing has emphasized the embodied nature of these forms of knowledge, how people take action through informal systems and social networks. And these forms of knowledge are increasingly being seen as something valuable by the global development network.

How do we claim the human infrastructure we produce, and then also share it more widely? It is part of our communicative ability as humans that material objects take on symbolism which can circulate beyond the original social contexts of production. We don't have to give consent for people to use our ideas or images in public spaces. It's much easier to find examples out there that show how to exploit subcultures rather than empower them, given our capitalist economic system where everything that isn't copyrighted is fair game to manufacture and sell. I'd love to hear others' ideas about how to keep tacit knowledge tied to making communities of practice by making them more inclusive.

Monday, July 15, 2013

The Distance Between Bike Economics And Social Justice

In the museum auditorium, a white crowd of about forty fanned across the many rows of seats. Onstage were an elected official, Congressman Earl Blumenauer, beloved by the bike movement for his openly bikey stance on Capitol Hill; a city planner, Roger Geller, the bicycle coordinator for the Portland Bureau of Transportation; Elly Blue, a writer and publisher about to release her second book, Bikenomics; and the panel's moderator, Professor Jennifer Dill, a prominent bike researcher at Portland State University and the director of the Oregon Transportation Research and Education Consortium.

When I started reading about Richard Florida's creative class theory in 2008, I thought maybe it was a coincidence that the bike movement's emphasis on infrastructure matched Florida's core idea: if you build it, they will come. That is, if politicians want to attract desirable, talented residents/consumers to their regions in the post-industrial, idea/upscale consumption economy, they must invest in the urban design elements that are as honey to these worker bees. Naw, I thought, the bike has way too much democratic potential to be reduced to a marketing tool. But I keep hearing powerful people like Congressman Blumenauer characterizing bike projects as a strategy to "attract talent," bringing "the best and the brightest" to places like Portland. In March, I heard the mayor of Indianapolis make similar remarks at the League of American Bicyclists' National Bike Summit that was this year themed "bikes mean business." I'm hearing a lot of consensus that a good way to convert people to bikes is to convince them that bike projects will raise their property values.

It seems like the bike movement, or at least its policy arm, has decided that their goal of getting more people on bikes is not in conflict with the goal of making urban neighborhoods more expensive, and I am baffled by how openly they make this claim. Aren't policymakers and lobbyists supposed to at least pretend that their pet projects have benefits for more than one group? And shouldn't livable neighborhoods be affordable? Because we're not all homeowners, and I don't see a lot of value in rents that skyrocket because more people are choosing to ride bikes. Maybe the city should be compensating us urban cyclists for our contribution to the marketable landscapes they crave.

If influential people have decided who, exactly, they want to attract to cycling, maybe the question we should be asking is if you build it, who will be replaced? The drive to bring in desirables leaves aside the question of who gets categorized as undesirable. I wonder if an unspoken goal of bike advocates uncomfortable with race, class, and cultural difference is to create urban zones free of these problems by simply vanishing, through the unquestionably objective means of the market, people unlike themselves. After all, using urban planning to rid cities of undesirables is nothing new. I hope, though, that folks will reconsider whether is is too hard to convince existing city residents that riding a bike is a good thing. Is it better that they be replaced by outsiders who already have that extra spending power to buy more bakfiets for the bicycle boulevard?

I had a lot to think about as I rode up to North Portland, passing through the neighborhood around Emanuel Hospital that had been razed as an urban renewal zone in the 1970s, biking up the controversial lane on N Williams Avenue. I thought about Geller's comment that what we need here in Portland to really get more investment in bike infrastructure is an urban renewal zone. I believe he was referring to some local funding terminology, but why is such a loaded phrase still in official use? One community's Voldemort is another's Harry Potter, and it matters who gets to decide what is failed urban policy and what needs another try.

At Peninsula Park, a group of several hundred people stood around a gazebo while speakers lined up to share their anger and concerns through a megaphone. One woman said that she saw a ride of 11,000 cyclists passing a few blocks away, but there were only a few hundred people here at the rally. I had seen the ride, too, and didn't put two and two together until later that it was Cascade Bicycle Club's Seattle to Portland ride arriving in the city. I thought it was a little unfair for her to single out cyclists as a group absent from the rally, considering how many people had biked there like myself.

When we went out to march, we walked along Albina, then Killingsworth, then turned onto Vancouver. The stream of cyclists I'd seen earlier, and that the speaker had mentioned at the rally, was still trickling down Vancouver, against the flow of the demonstration. I was talking to friends when we heard shouting and saw a marcher using his body to block the path of a cyclist traveling in the bike lane. "Peace!" someone called out, as others intervened to end the altercation. "Peace!" In that moment, the distance between bike economics and social justice shrank to the distance between one frustrated man and the mobile symbol of a system stacked against him.

Even if the city, the bike movement, the people in power who make funding decisions about street infrastructure, don't want to talk about the uneven politics of who gets to decide what transportation counts and who should benefit from improvements to public streets, the demonstrator blocking the path of the cyclist with his body made clear how this symbol of outside wealth stimulating the local economy, this "attractor of talent," the envy of Rahm Emanuel and other mayors who "want what Portland has," was too much to handle on a day when the country was mourning yet again the unequal treatment African-Americans can expect from our public institutions.

It all comes together in the street, whether you're guiding the political machine and reaping the benefits or struggling as some undesirable who will soon be replaced by someone worth more. Because we all know that some bodies matter more than others.

Wednesday, July 3, 2013

On Returning To Portland And Bike Justice

|

| We are the connections between the places we inhabit. |

When I first moved to Portland, Oregon in August 2001, I was 17 and had never lived outside the Mexican enclave where I grew up in postcolonial Orange County. Suddenly I was sharing a dorm with kids from very different backgrounds, and I thanked my lucky stars that my older sister had had cable so that I could at least reference the Nickelodeon shows they'd watched during their more secure childhoods. Without the rock en español station whose airwaves had drifted up from Tijuana to my bedroom at home, I started listening to hip hop radio because if I closed my eyes the songs reminded me of the music I heard from cars passing outside our apartment in the Villas de Capistrano.

Then I fell pretty quickly into a social life beyond anything I'd known as an introverted teenager, and set aside my anger about the racist situation at home and my questions about my own identity as a non-native-Spanish-speaking-but-brown product of a Mexican-American union. The radiant heating that emanated upwards through my linoleum dorm room floor soothed me into dreamy states I'd never achieved at home, where my childhood anxiety spiked my veins with panic every time I heard a police siren. I spent my time making friends laugh, getting deeper into my longstanding interest in recycled fabrics, and, eventually, riding a bicycle. Occasionally I had opportunities to lament my rusty Spanish with fellow Latinos, but I mainly conceived of my culture as an aesthetic.

When I grew restless in Portland and decided to start graduate school in Southern California, I didn't anticipate embarking on an adventure that reconnected my teenage sense of indignation at the ways people keep each other down with my newer, embodied love of riding a bike. But that's what happened, and why my dissertation is about bikes, the (un)desirability of particular bodies, and the impact of social life on Los Angeles' streets. I see myself now as an advocate for bike justice, commenting on the embeddedness of bicycling and other sustainable practices in historied landscapes of race and class bias.

I moved back to Portland in June. Some things I've encountered since moving back:

1. A motorist honking and screaming at me and my boyfriend, presumably for riding bikes.

2. A pedestrian halting in the crosswalk, I think because she didn't believe I would stop my bike at the stop sign I was approaching.

3. A discussion group for mixed race activist women.

4. An organization fighting to bring the benefits of the city's bike economy to workers and people of color.

5. A prominent local bike advocate dismissing social justice as a relevant concern for the bike movement here, to a national audience.

6. A motorist waving me through at a four way stop where I did not have the right of way.

I met a new collaborator yesterday who shared his intriguing hypothesis about why something like "social justice" might seem unpalatable to people here: perhaps Portland absorbs the white flight of people fleeing more complicated situations in other regions. Then when they settle here, they don't want to hear about race/class inequality; isn't that what they moved here to avoid? It rang true for me as I reflected on the endless bungalows of this small-town-feel city, a controlled environment à la Disneyland but with bikes. I thought about my own escape here in 2001, and what a different person I am from the Adonia who moved to Long Beach in September 2007. I've been co-produced through the places I've inhabited, angry about the racism of my hometown, carfree because of a seed planted in Portland and cultivated at the L.A. Eco-Village, and concerned about green gentrification because of the time I spent in Seattle.

I moved back here because Portland has the opportunity to buck the green segregation that is spreading the benefits of economic recovery to some communities and shunting others to the outskirts of our increasingly expensive metropolises. It's clearly been a national leader in bike innovation. Can it also be a national leader in fostering a diverse future for American cities? Can there be a sustainable urbanism that confronts rather than displaces urban history? My training in anthropology, and my life as a cross cultural person, make me want to grapple with the less material aspects of urban experience, the feelings, the cultural attitudes, the expectations of our fellow road users. This city can be a rich field in which to experiment with the question of why, even now, people have "one less bike" stickers on their cars and feel threatened by cyclists. I want to help challenge the idea of a homogeneous Portland where everyone complies with the same norms. We hybrids exist, here in Portland and all over the world. There will be no Main Street, U.S.A. without us, and there never has been.

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

Does Culture Matter In Urban Design?

Back in the early days of my academic discipline, cultural

anthropology, researchers worked to document what they saw as a

rapidly vanishing diversity of cultures. Ethnographers fanned out

across continents, recording ritual practices and languages, often

conveniently ignoring the massive changes their interlocutors' lives

had already undergone through participation in global political and

economic systems. Then we realized something: culture doesn't

disappear, it changes. And all cultures aren't dwindling to one,

western, homogeneous hegemon. Culture isn't something bounded by an ethnicity or a location; it travels, and demonstrating one's familiarity with a particular culture can be a way of showing power across lines of race, class, and geography. Culture is a term that describes the shared systems of meaning and value that regulate our interactions with friends, family, and strangers. It can seem invisible to us, even as we deftly maneuver our way through social situations that leave people unfamiliar with the prevailing culture stumped.

My research has focused on the immaterial phenomena that filter transportation choices; I've been trying to argue that in a given interaction between a road user and a road, there's a third element as well beyond individual-in-motion and built-environment-at-rest. There's also a scale of accepted behaviors, agreed upon uses, shared ideas about what should happen in given spaces. Other words that might describe this are manners, customs, norms. In my field we call it habitus, and I've been writing about it as human infrastructure. It seems to me, as an anthropologist, that this is precisely what drivers complain about: that bicyclists are challenging their street culture. But their concerns get dismissed as hooey by people who are accustomed to believing that the built environment is the key to determining behavior ("if you build it, they will come"). That's a conundrum to me: if we need to change the built environment to get people to change their behavior, aren't we acknowledging that changed behavior is the end goal? If we want them to come, maybe we should be thinking like them, building cultural networks of shared meanings and values rather than expecting physical changes to make the shift in transportation habits we desire.

Often I see "culture" used as a gloss to talk about identity groups, and I wonder if some of my readers will say to themselves that adding culture into urban design is accomplished through government grants going to nonprofits whose aim is to empower a particular community of color. That's not quite what I'm getting at. Actually a lot of those groups have their hands full trying to achieve American middle class status for their communities, and the bike thing, for all the aspirational aims of the cycle-chic-bikes-mean-business-biking-in-heels lobby, still looks like something for freaks or poors. If you've staked your leadership on showing the way for your constituency to get away from being seen as freaky or poor, would you choose biking as something to support? What I mean by culture is not identity politics; I mean the subtle distinctions we perform to show those around us that we "get" it, that we're normal humans complying with the standards they expect to keep them feeling like we're trustworthy individuals.

My research has focused on the immaterial phenomena that filter transportation choices; I've been trying to argue that in a given interaction between a road user and a road, there's a third element as well beyond individual-in-motion and built-environment-at-rest. There's also a scale of accepted behaviors, agreed upon uses, shared ideas about what should happen in given spaces. Other words that might describe this are manners, customs, norms. In my field we call it habitus, and I've been writing about it as human infrastructure. It seems to me, as an anthropologist, that this is precisely what drivers complain about: that bicyclists are challenging their street culture. But their concerns get dismissed as hooey by people who are accustomed to believing that the built environment is the key to determining behavior ("if you build it, they will come"). That's a conundrum to me: if we need to change the built environment to get people to change their behavior, aren't we acknowledging that changed behavior is the end goal? If we want them to come, maybe we should be thinking like them, building cultural networks of shared meanings and values rather than expecting physical changes to make the shift in transportation habits we desire.

Often I see "culture" used as a gloss to talk about identity groups, and I wonder if some of my readers will say to themselves that adding culture into urban design is accomplished through government grants going to nonprofits whose aim is to empower a particular community of color. That's not quite what I'm getting at. Actually a lot of those groups have their hands full trying to achieve American middle class status for their communities, and the bike thing, for all the aspirational aims of the cycle-chic-bikes-mean-business-biking-in-heels lobby, still looks like something for freaks or poors. If you've staked your leadership on showing the way for your constituency to get away from being seen as freaky or poor, would you choose biking as something to support? What I mean by culture is not identity politics; I mean the subtle distinctions we perform to show those around us that we "get" it, that we're normal humans complying with the standards they expect to keep them feeling like we're trustworthy individuals.

A few weeks ago, I was waiting in the

Stockton, California train station, and I saw that there was a coin

operated lock on the restroom. As I thought about getting out some

change, a woman saw me coming and held the door open, explaining that

I'd otherwise have to go get a token from a ticket agent. This door

had been designed to prevent non-travelers from using the restroom,

but people were using it "wrong," so to speak, keeping it open with their bodies so that others could avoid a hassle. I was an

authorized customer, so I would have been given a token by the ticket agent. But why

follow the door's rules when there was a person there to hold it open

for me? In any case, it would have been very odd for me to refuse the lady's offer.

The tensions that we experience on city streets follow the same script: a designed environment, at least two parties, and the expectations of those parties as to how each is going to use the space. Those expectations may be based on the built environment they're inhabiting, or they might be based on some idea of courtesy that person picked up in some completely different built environment. Every bicyclist I know has a lot of stories about times they've been waved through four-way stops by drivers who thought they were doing a kindness, just as every bicyclist I know has a lot of stories about being screamed at or worse by drivers who reacted more or less violently to the fact that the bicyclist had a different idea about how to use the road than they did. People don't react in the same way to the same intersection; people enact different transportation cultures in the same spaces.

Maybe bicycling is attracting

people who see change not in community but in design; maybe it

is attracting people who come together around technical skills rather than

identity politics. Meanwhile, "bike culture" is being trivialized, pipe

cleaners poking out of a helmet, a quirky cherry on a concrete

sundae. While this may feel comfortable for some folks, culture does

more than decorate built environments. It is an embodied experience,

reproduced through social life, that feels unchanging, even as it subtly shifts. Pierre Bourdieu likened it to "a train bringing

along its own rails." We should be brainstorming more about

transportation culture and how it fits in with other kinds of standards

for success here in the U.S. Transportation cultures, like cultures in general, change. What might

be seen as a streetcar city one decade could become a car city the

next; what seemed like a terrible place to bike could spark all kinds

of exciting bike life.

I've realized over my years as a bike advocate that most of my collaborators take for granted that the only way to change how people use streets is to change the street materially through infrastructure projects. Clearly some of us have figured out a different transportation culture, cause many of us are getting around on bikes by choice or by necessity, but even community projects that build human infrastructure get reduced to a call for more street redesign. CicLAvia, where tens of thousands of people come out to walk and ride bikes, gets used to say that if only there was bike infrastructure, people would ride in L.A. For example, in a piece LA Streetsblog posted last year about mayoral candidates' views toward CicLAvia, Kevin James commented that he was impressed by "the sheer size of the crowd, which I believe speaks volumes about the number of Angelenos willing to use their bicycles more often as their primary mode of transportation if the City were more bike-friendly." More recently, a friend forwarded me an article from The Atlantic that speaks positively about CicLAvia, but the author, Conor Friedersdorf, observes that "seeing the masses out on bikes hinted at how a safe system of bike lanes could improve Los Angeles, a city with temperate weather, a fitness obsession, and gridlocked traffic." It's strange to hear these "if you build it, they will come" statements from speakers who also note the tens of thousands of people around them.

Culture is playing a role in how we use and imagine our streets. Shouldn't it be something we discuss as we work to change them?

I've realized over my years as a bike advocate that most of my collaborators take for granted that the only way to change how people use streets is to change the street materially through infrastructure projects. Clearly some of us have figured out a different transportation culture, cause many of us are getting around on bikes by choice or by necessity, but even community projects that build human infrastructure get reduced to a call for more street redesign. CicLAvia, where tens of thousands of people come out to walk and ride bikes, gets used to say that if only there was bike infrastructure, people would ride in L.A. For example, in a piece LA Streetsblog posted last year about mayoral candidates' views toward CicLAvia, Kevin James commented that he was impressed by "the sheer size of the crowd, which I believe speaks volumes about the number of Angelenos willing to use their bicycles more often as their primary mode of transportation if the City were more bike-friendly." More recently, a friend forwarded me an article from The Atlantic that speaks positively about CicLAvia, but the author, Conor Friedersdorf, observes that "seeing the masses out on bikes hinted at how a safe system of bike lanes could improve Los Angeles, a city with temperate weather, a fitness obsession, and gridlocked traffic." It's strange to hear these "if you build it, they will come" statements from speakers who also note the tens of thousands of people around them.

Culture is playing a role in how we use and imagine our streets. Shouldn't it be something we discuss as we work to change them?

Wednesday, June 19, 2013

Bike Infrastructure Is Political Too

|

| Deep in the bowels of the Senate on lobbying day at the National Bike Summit in March. |

Opposition to bicycling makes for some strange bedfellows, bringing together community advocates and conservative commentators. There was a recent video where Wall Street Journal editorial board member (and Pulitzer Prize winner) Dorothy Rabinowitz made some claims about New York City's new bike share program being part of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's larger political platform. Some of Rabinowitz's claims were clearly outlandish, such as the notion that she represents the views of a majority of New Yorkers, but the rumbling agreement among bike people that she is a nutso got me to thinking: what makes it so hard for bike people to believe that bike infrastructure could be political? I have heard many bike advocates talk about the need for political will to expand bicycling as a viable mode of transport. And yet, in this case of clear mayoral support for bicycling, we deny that putting political will behind bikes is a political choice? Dorothy Rabinowitz was correct; the bike share program does fit into a larger mayoral agenda for New York. She is right that cyclists are being "empowered by the city administration with the idea that they are privileged, because they are helping, they are part of all the good,

forward-looking things." We just disagree with her that bicycling is a bad thing to promote.

It's key to note that Rabinowitz's view of bicycling as a menace used to be very conventional, but now it goes against the new consensus of advocates, politicians, and increasingly the business community, that supporting bikes is a good economic development strategy. This is how politics works: when the machine is being used to promote something you don't like, you call it bad. When it's used to promote something you like, all's well with democracy.

I'm often surprised by the lack of critical urbanism in bicycle circles, as though the bicycle's inherent goodness dazzles the eyes so severely that boosters are blinded to the very clear legacy of urban redevelopment erasing the working poor. What gave bike people the idea that changes to the built environment would benefit anybody but those already adept at manipulating public services for their own good? I think it's that they are often people who were raised to see government intervention as a boon, something that you should go out and lobby for as a good citizen. Here's the thing: not everyone benefits from state-sponsored infrastructure projects, which tend to serve the interests of powerful people. Infrastructure projects that underpin development create winners and losers, and deciding who wins and who loses is a political process. Just because bike interests are starting to win doesn't mean that the process has changed.

Many bike advocates appeal to a rationalistic notion that urban planning can fix our social ills, that we can design built environments that repair the longstanding cracks in our segregated communities. But going back to the era of Baron von Haussmann's plan for Paris, cities have used urban plans to rid city centers of undesirables. An appreciation for urban life grew alongside this desire to control it, from Thomas De Quincey and Charles Baudelaire slumming around with prostitutes, to the impassioned observations of Walter Benjamin, to the Marxists of the Situationist International mapping quartiers scheduled for demolition (on a sidenote, have you noticed how often people who deal in urban design, not political protest, appropriate "Sous les pavés, la plage"?). More recent environmental justice struggles have made the same point, with a resounding

We've known for a long time that the benefits of urban redevelopment projects tend to land in certain laps while the burdens are borne on the backs of others.

We know, too, that the people who make urban neighborhoods interesting might not be the ones who own property and hence control the destinies of those spaces.

Thinking that the only way we can promote bicycling to a wider population is by allying ourselves with those who run an economic machine that relies on and ignores the exploitation of less empowered people is a pretty poor use of imagination. We can laugh and point when something as wacky as Rabinowitz's video circulates. But while we can agree that she missed the point, her rant shows how bikes and bike infrastructure projects fit into other kinds of agendas. We may see ourselves as the underdog, but sometimes bike advocates come across like a kid who has all the toys in the world except for the one he wants the most.

Power flows through a grid. As bike advocates, we may benefit from having power on our side, but organizations that use a "bikes mean business" strategy should be prepared to hear bike projects get blamed for gentrification. This is explicitly what you are calling for: a city where only those who can afford to, as participants in a creative economy, enjoy the idea of complete streets. (Whether those people buying and selling the idea of the bicycle actually plan to change their transportation habits is another question entirely.) With such a history of urban infrastructures benefiting those already in power, what makes us think that bike-specific projects would somehow be exempt from this fact?

If we reduce the fun, exciting, and creative practice of bicycling to infrastructure projects that give an excuse to charge higher rents from desirable urban creatives, who benefits? If bicycling is going to be for everyone, it's because we're going to intervene in urban business as usual, not hand over our bodily knowledge to people who are going to sell it back to us through bike-themed condos.

Friday, May 31, 2013

Things that are More Adult than Driver's Licenses

It's not hard to find examples of Americans equating adulthood with driver's licenses/driving/car ownership. I came across one yesterday on a ladyblog written by women based in New York (where I hear people walk a lot?) that tends to pander to readers who, I've assumed from the comments, live in places where driving is the norm. I started thinking about how strange it is that people present the driver's license as evidence of independence and adulthood, considering the childishness of our American belief that nothing matters more than our freedom to drive.

Here are some better benchmarks of adulthood than driving, presented after the fashion that is traditional on late night television:

10. Waiting for a bus for two hours

9. Noticing that the "zombie apocalypse" is code for fears about global warming

8. Paying bills

7. Talking to your neighbors

6. Realizing that not everybody experiences the world in the same way

5. Choosing a place to live based on ecological considerations rather than some debt-driven homeownership fantasy (here's looking at you, California desert suburbs)

4. Rethinking the mentality that you can buy your way out of problems

3. Making choices not to impress your peers but to impress yourself

2. Recognizing the connections between your individual actions and the world around you

1. Taking responsibility for the effects of your choices

Contrary to longstanding opinion, growing the fuck up is in fact a cure for those pernicious "Summertime Blues."

Here are some better benchmarks of adulthood than driving, presented after the fashion that is traditional on late night television:

10. Waiting for a bus for two hours

9. Noticing that the "zombie apocalypse" is code for fears about global warming

8. Paying bills

7. Talking to your neighbors

6. Realizing that not everybody experiences the world in the same way

5. Choosing a place to live based on ecological considerations rather than some debt-driven homeownership fantasy (here's looking at you, California desert suburbs)

4. Rethinking the mentality that you can buy your way out of problems

3. Making choices not to impress your peers but to impress yourself

2. Recognizing the connections between your individual actions and the world around you

1. Taking responsibility for the effects of your choices

Contrary to longstanding opinion, growing the fuck up is in fact a cure for those pernicious "Summertime Blues."

Sunday, May 12, 2013

What is a Bike Movement? Here's the Deal with labikemvmt.org

When I started my anthropology PhD program in September 2007, I planned to study the politics of rock en español. Then my bike and Los Angeles intervened. I didn't like the way motorists treated me when I biked in L.A. I also knew that there was major status displayed in transportation, and that bicycling could be a symptom of just how marginal some people of color were. Something needed to change in L.A.'s street culture, and I wanted to help. But I didn't know how change happened. I started formulating a new dissertation project in spring 2008, when I decided to make becoming a bike activist into an

ethnographic project.

For the next three years, I learned about how culture change happens through collaborating on some projects that experimented with bicycling in L.A., most notably CicLAvia and City of Lights/Ciudad de Luces. Then, when I moved away from L.A. to write the dissertation in 2011, I realized that those projects were able to emerge not just because some people had bothered to organize them, but because they built on the human infrastructure created by the L.A. bike movement. People had been fighting for years to show that not only could you bike in L.A., you could have FUN (F.U.N.?). It could be something that made people feel like part of a secret world, it could be something that connected people to the city's history, it could be something that you did in a costume, it could be something that you did with your kid, it could be something that changed your community. At the same time, it could be something you did because you couldn't afford to do what you really wanted, which was drive, or because riding a bike was just what people did back home.*

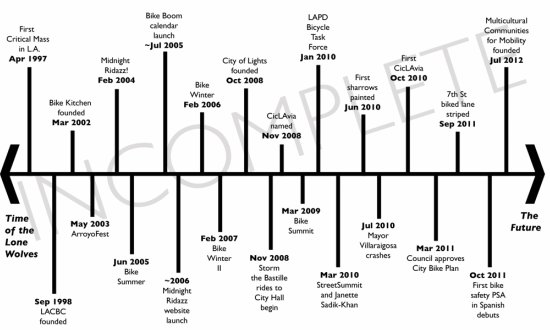

My dissertation is called "Body-City-Machines: Human Infrastructure for Bicycling in Los Angeles." Dissertation committee-willing, I should be done with that project in about a month. Because I don't really finish projects before I start new ones, I got this idea in my head that there needed to be more documentation of the kind of cumulative effect I experienced in organizing bike projects in L.A. There's a lot of information online about different projects and groups in L.A., on both the culture and advocacy side (any bike nerd who hasn't spent hours on Don Ward's amazing Midnight Ridazz Ride Calendar should go there immediately), but I thought it might be useful to put together a timeline of events people considered important to the development of a bike movement. I also knew that because I'd chosen to make my ethnography about my own trajectory as a bike activist instead of about the history of the L.A. bike movement, there were many things I didn't even know about. I was going to need a lot of help.

I bought the URL labikemvmt.org as a starting point. Then I put together an event for April 12 at the L.A. Eco-Village that would provide some oral history about the particular thread that I have followed in my own understanding of key elements of the L.A. bike movement:

As soon as I had announced the event, I started getting feedback that I had not invited key people who had insight into the bike movement. My first response to that was like, no shit Sherlock, ain't no way I can include the entire universe of people who have made bike change happen in L.A. in one event. Then I got over myself and started thinking about two important questions: Who counts in a social movement? Who gets credit for culture change?

Who counts in a social movement?

The event I'd put together, "Building a Bike Movement in Autopia," started with a panel of the usual suspects, so to speak: the founders of LACBC and the Bike Kitchen (Ron Milam, Jimmy Lizama, Ben Guzman, Kelly Marie Martin), people who had been around for the early days of Midnight Ridazz (Marisa "MaBell" Bell, Don "Roadblock" Ward), people who have done bike policy work in L.A. (Colin Bogart, Aurisha Smolarski-Waters, Alexis Lantz), and people who are bringing biking from places beyond the Bike Kitchen-Bikerowave-Bike Oven sphere like South L.A. to the forefront of the movement (Tafarai Bayne, George Villanueva, John Jones III). Ron, who was also the facilitator, framed things as an improv-style "yes, and" exercise, where people could interrupt each other after someone had talked for a few minutes to add their perspective. People had a great time talking and listening. There were about 60 people sitting around the ecovillage lobby, and I for one felt electrically charged. Then, with much left to say, we cut it off so we could have time to add events to a group timeline I'd posted around the room.

Things got loud! I've posted the updated timeline to labikemvmt.org, feel free to make suggestions there.

As I circulated and talked with different bike folks I'd never met, I learned that thanks to Sahra Sulaiman at LA Streetsblog, there were some people in attendance I hadn't expected to see that night, like J. Swift of Black Kids on Bikes and Stalin Medina of Watts Cyclery. Then I was bowled over to see Yolanda Davis-Overstreet, the force behind the documentary RIDE: In Living Color, who I'd been starstruck to meet at the National Bike Summit in March. I think, in retrospect, the event I organized on April 12 was more of a performance of the fuzzie-wuzzies people can feel when they're part of a subcultural network than it was an inclusive statement about the bike movement in Los Angeles. I wanted to show a particular community to other bike scholars, and feel a part of it myself again after living away from L.A. for two years. The other side of community belonging, though, is exclusivity. The evening became disorienting for me when I was reminded that the L.A. bike movement seems exclusive and privileged to some people. I felt pretty invisible, as a self-identified woman of color who has been arguing for equity in bike advocacy in L.A. and beyond since 2008. But I also felt like maybe it was an accomplishment that I'd created a moment where a room full of bike advocates would clap enthusiastically when Stalin said that Latinos riding bikes in South and East L.A. should be seen as part of the movement too.

Who counts as part of a bike movement depends on who you're talking to. Not everybody has the means to be part of the conversation, when the people talking are part of a limited circle. Bike advocates who have privileges of race, class, gender, education, social connections may not connect with every cyclist using streets in L.A., but they do speak for them in policy processes. Is it up to a movement and go out and recognize people as participants? Or is it up to like-minded people to find each other? Both? Maybe it makes more sense to talk about a multi-sited movement, where people developed their own communities around bicycling, rather than one cohesive thing to which many people belong. In a city like Los Angeles, where there are huge disparities between what's happening in different parts of the metropolis, it's an open question how much concurrent developments influenced each other.

I'm now thinking about the urban L.A. bike movement as having three threads: culture, advocacy, and usage. The people living these threads cross over between the different categories all the time, although not everyone does.

Culture

The first time I experienced L.A. bike culture was riding in from Long Beach for the second All City Toy Ride in 2007 that met up at Olvera Street. It was a powerful turning point for me because I saw with my own eyes how many people wanted to have fun on bikes in L.A., and I saw them doing it not on the beach, not on some creek trail, but in the historic urban core of this so-called non-city. Based on what I've found from researching and talking to people, I would say that downtown L.A.'s messenger culture can take the credit for starting a social life around bicycling in the central city. Then Critical Mass brought together people who were interested in bike commuting but weren't necessarily part of the messenger culture. After the downtown messengers were no longer the only people socializing around urban cycling, one way to consider the growth of bike culture in L.A. would be linking it to the three oldest bike co-ops: the Bicycle Kitchen (East Hollywood), the Bikerowave (Westside), and the Bike Oven (NELA). A keen observer will note that a lot of the info I have on the timeline as of now is skewed toward the Bike Kitchen's circle of influence, because that's what I was more socially connected with as an ecovillager. I'm especially hoping to hear from folks who have key events in mind associated with the other co-ops, and from co-ops that started after the mid 2000s bike boom.

Advocacy

Ron Milam and Joe Linton had already been working in sustainability advocacy before they came together through Critical Mass in the late 90s. So Ron was ready to listen when Chris Morfas at the California Bicycle Coalition hinted that L.A. needed its own bike coalition. LACBC was founded in 1998. Many cyclists were politically activated by the DNC Critical Mass arrests in 2000 that disproportionately targeted women. Bike blogs, and especially the mobilization around the Bike Writers Collective that Stephen Box instigated, show the growth of political organizing around L.A. cycling after 2007. By the time I showed up in L.A.'s advocacy scene in September 2008, it was gaining speed. Speaking of bike advocacy, Angelenos should fill out Bikeside L.A.'s bike friendliness survey, which is accepting responses till Tuesday.

Usage

This refers to the fact that there've been bodies on bicycles getting around L.A. since the first bike boom in the 1890s. Maybe they weren't organizing themselves around urban cycling, like developing styles together or lobbying at City Hall, but their bodies have been out there on the streets whether motorists liked it or not. By 2005, when Dan Koeppel published his "Invisible Riders" article about Latino cyclists in Bicycling, urban bike culture and advocacy in L.A. were flourishing, but without necessarily reaching cyclists beyond subcultural circles. For me, as an activist and a researcher, thinking of bike usage as a component of a bike movement is about radical inclusion. It's about turning around and confronting our movement with its own tendencies to reproduce existing power structures and saying, no, we are going to go out of our way to call attention to the other people who aren't getting the credit for culture change that comes our way more easily. To say that the bodies of jornaleros, or the people biking in Inglewood and Boyle Heights, matter less than the mobs of Ridazz in this street story is to give in, yet again, to the idea that the city belongs to one group over another. The city is ours because we put our bodies on the line to make it what it is. No loft developer can design that into the street, no matter how much green paint they throw down. If we, as a movement, turn our backs on this tendency for human practices like urban cycling to become sites of value for some people and not others, we are the ones being exclusive. We are the ones making those riders invisible. When we don't expect to see cycling in places like Watts, we overlook the organizing going on there, the ways that people are using bikes to empower their communities.

Who gets credit for social change?

As I've been amassing dates, events, and names for the timeline, I've spent a lot of time searching through internet archives and seeing how newspapers like the L.A. Times portrayed alleycats in 2003, when they tagged it as "entertainment," and CicLAvia in 2013 being associated with public health. Talking about a social movement means talking about change, and change happens in ways that are hard to quantify. We decide, afterwards, what was important, what was a turning point. Sometimes we feel the excitement in the moment, and we think, everything will be different after this. Sometimes it's really clear who had an idea, and how that idea had ripple effects beyond an immediate circle. Sometimes people with more privilege, due to gender, education, race, any number of factors, position themselves to be the recipients of credit when there are others behind the scenes that everyone would admit had something to do with making things happen. How do community-based projects get converted into individual credit? There's not always a clear answer to the question, but the people who get named in newspapers, in conversations, in policy documents, travel into new situations where they can have an impact beyond the people who did not get credit.

It is a well-documented fact that women do not get as much credit for their activism as men do. For example, Lee Sartain's 2007 study of women in Louisiana's NAACP from 1915 to 1945 is called Invisible Activists. Closer to L.A., Mary Pardo's 1998 study called Mexican American Women Activists acknowledged the way that men frequently took the public stage in the Chicano movement. My point here is that who gets "credit" for projects tends to follow lines of power in a given situation. For this reason, I think it's especially important to consider issues like race, class, and gender in determining who counts in something like a bike movement. The timeline I've posted on labikemvmt.org is an attempt at tracing a chronology of accumulated energy more than it is a catalog of credit.

Many thanks to all the people who came to the Biking Autopia event, especially Ron Milam who acted as facilitator and Kelly Marie Martin, who gave the timeline a big starting boost. I'm also grateful to the scholars on the Bicicultures listserv who contributed their thoughts to the question of what counts as participation in a bike movement, to Ben O'Donnell for coding the timeline, and most of all to Sarah McCullough, who brought the idea of an archive to my mind and who continues to be an invaluable collaborator.

*Note: I've never investigated the roadie or mountain bike cultures in L.A. I know there's definitely crossover between the urban bike movement and those social networks, but I'm not the person documenting them.

For the next three years, I learned about how culture change happens through collaborating on some projects that experimented with bicycling in L.A., most notably CicLAvia and City of Lights/Ciudad de Luces. Then, when I moved away from L.A. to write the dissertation in 2011, I realized that those projects were able to emerge not just because some people had bothered to organize them, but because they built on the human infrastructure created by the L.A. bike movement. People had been fighting for years to show that not only could you bike in L.A., you could have FUN (F.U.N.?). It could be something that made people feel like part of a secret world, it could be something that connected people to the city's history, it could be something that you did in a costume, it could be something that you did with your kid, it could be something that changed your community. At the same time, it could be something you did because you couldn't afford to do what you really wanted, which was drive, or because riding a bike was just what people did back home.*